S1E10: “The consensus unraveled”

Epilogue

This post is the final one of a series on the history of how economists model the future with the Ramsey formula, based on joint work with Pedro Garcia Duarte. See episode 1 , episode 2, episode 3, episode 4, episode 5, episode 6, episode 7, episode 8 and episode 9. Full Paper here.

Alan Manne was the referee who suggested IPCC economists had taken a 'prescriptivist' view of discounting while he defended a 'descriptivist' one. Manne was already using the dichotomy during the IIASA 1993 workshop, and probably even before. One of the papers he presented at that workshop opened with a section titled “Time preference: prescription vs description.”

In the wake of the 1996 IPCC report, Paul Portney (the newly minted RFF president) and John Weyant (Energy Modeling Forum director and IPCC lead writer) put together a fresh conference on discounting. Both had participated in these debates since the 1970s. They circulated the IPCC chapter to potential attendees, noting that 'in the mid-1990s, Lind's apparent compromise seemed to unravel.' Their questions probed how to handle projects with centuries-long impacts and whether discounting and cost-benefit analysis were really the right framework to tackle climate change or nuclear investments. The contributions were published in 1999.

The conference was a mix of familiar faces and newcomers to the field. Veterans included Schelling, Cline, Manne (whose paper again led with the prescriptive vs descriptive distinction before recasting discounting choices in terms of efficiency and equity), Nordhaus, Dasgupta, Goran-Mäler, and Arrow. True to form, Arrow penned the opening chapter. By this point, he'd delved deeper into ethics and contributed a piece on 'morality' and discounting.

The contributions from newcomers highlighted how quickly the dynamics of the debates were shifting with the rise of climate modeling. While I'm still working out how to pin it down precisely, it seems the stabilization of the Ramsey equation (which participants recall was a hot topic during the conference) and the emergence of a rift between two approaches reopened Pandora's box. Every parameter of the formula, as well as the framework from which it emerged, became subject to renewed scrutiny.

Maureen Cropper and David Laibson addressed the growing research on hyperbolic discounting that had gained momentum since Richard Thaler’s work. The concept of declining discount rates for decisions extending far into the future had been previously considered in Schelling-Manne-Nordhaus-Cline exchanges. However, the advancement of behavioral economics and laboratory reexaminations of individual time preferences provided a more structured approach to this line of inquiry. At the same time, new axiomatic foundations for models involving indefinite futures or extinctionwere being developed.

Lind's proposition that the discount rate was not the appropriate mechanism to account for risk faced challenges. Martin Weitzman presented preliminary thoughts during the conference, anticipating later collective work on gamma discountingand risk-adjusted discounting. The paper by Portney and Kopp aligned with Schelling's skepticism regarding the adequacy of discounting and its utilitarian underpinnings as a framework for addressing intergenerational justice. Adapting or challenging the utilitarian foundations on which discounting rests then developed into a flourishing area of research.

But these various lines of research constitute the present of discounting, which lies beyond our scope. They are addressed in recent surveys that appear regularly, often intertwined with many of the contributions covered in this series. So, you might wonder, what's the point of digging into history when we could just read these surveys? While Pedro and I have fleshed out the narrative of the Ramsey Formula's rise, we're still mulling over the lessons to draw from it. Here are my tentative thoughts (for which Pedro bears no responsibility):

(1) Context is key: The discounting techniques and debates we've covered are rooted in a long-standing quest for a rational, scientific approach to public investment - first in the US, then worldwide. From the 1970s, it was paired with a specific focus with the distant or deep future. these techniques, debates, and the ebb and flow of concerns (like risk, intergenerational inequality, and axiomatic consistency) are also shaped by specific research questions: water investment in the 1950s, energy investment and evaluation investment in developing countries in the 1970s, and climate change from the 1990s onward.

(2) This historical perspective I hope highlights how models, tools, concepts and categories develop and spread: Arrow’s pivotal role in disseminating the Ramsey formula, or Manne's behind-the-scenes influence in framing disagreements about its application. It's got me wondering: would economists today still identify as prescriptivists or descriptivists? Would they find these labels useful? The archives reveal that neither group is a united one. For instance, Nordhaus, Manne, and Schelling all advocate setting discount rates based on observed behavior - be it market data, macro time series, or behavioral surveys. But their justifications are different.

(3) The status of ambiguity in science: reading a survey on discounting often leaves one with a persistent sense of ambiguity. These are frequently structured as a menu of approaches to the problem of comparing present and future flows, and it's not always clear how to relate them to one another or identify the sources of disagreements. The Ramsey formula isn't immune to this ambiguity. Our research aims to unpack three sources for it:

First, there's the ambiguity in the development of the Formula itself. When we talk about the “Ramsey formula,” we're actually referring to two equations stemming from two frameworks. These are intertwined in Ramsey's work and later theoretical work, particularly Arrow's. The right-hand side of the equation is consistent, though the elasticity of marginal utility is sometimes interpreted as a risk aversion parameter, an inequality aversion parameter, or both. But the left-hand side is shrouded with ambiguity: when the equation is derived from the intertemporal utilitarian foundations Ramsey endorsed, it determines the social consumption rate or the social rate of time preference. But when it comes from the post-World War II optimal growth model, it's an optimality condition determining the rate of return on investment in the steady state.

Philosopher Paul Kelleher, who has a forthcoming book on the social cost of carbon and discounting, makes a clear distinction between the “Ramsey formula” from intertemporal utilitarian analysis and the “Ramsey rule” from optimal growth models. But for most of the 20th century the terms were used interchangeably without clear distinction. This blurring of lines largely stems from the back-and-forth between frameworks, as we saw in our account of the IPCC chapter's writing and revision (I'm still not sure which term to settle on - Ramsey formula or Ramsey equation).

The second source of ambiguity relates to the formula’s travels from theoretical to applied economics, in particular cost-benefit analysis. The IPCC chapter, aiming at applications to climate modeling, is a prime example. Here, the Ramsey formula ultimately determines “the discount rate,” whatever is it. The focus has shifted from precise model-based derivations to parameterization. For some economists, it was an ethical decision about social time preference. For others, it was a consumption rate derived from agents' behavior. Still others saw it as a calculated rate of return on investment, or simply a market rate.

The third source of ambiguity arises from comes from the constant juggling between theoretical and axiomatic consistency, ethical foundations, and tractability constraints in discounting discussions. While one aspect might take center stage in a particular work, the others are never far behind. And I hope this case study makes a strong argument for not dismissing tractability considerations in the history of economics. They need to be documented as carefully as other motives for choosing a model or tool. They're persistent, and they're shaping economists' practices in significant ways.

I see our job as historians as documenting those ambiguities rather than resolving them. I have no say in whether the ambiguities are a good or bad thing. But one takeaway from our research is that they make the Ramsey formula versatile, and made it a framework for separating or reuniting various lines of disagreement, and theoretical, empirical and ethical considerations. In the language of historians of science, its essential ambiguity made it a successful 'trading zone' (to borrow from Peter Galison) or a 'boundary object' (if you wish to channel Susan Leigh Star). There’s also growing research in the philosophy of science on model transfers, but it’s more focused on transfers across disciplines, which isn’t quite what this story is about).

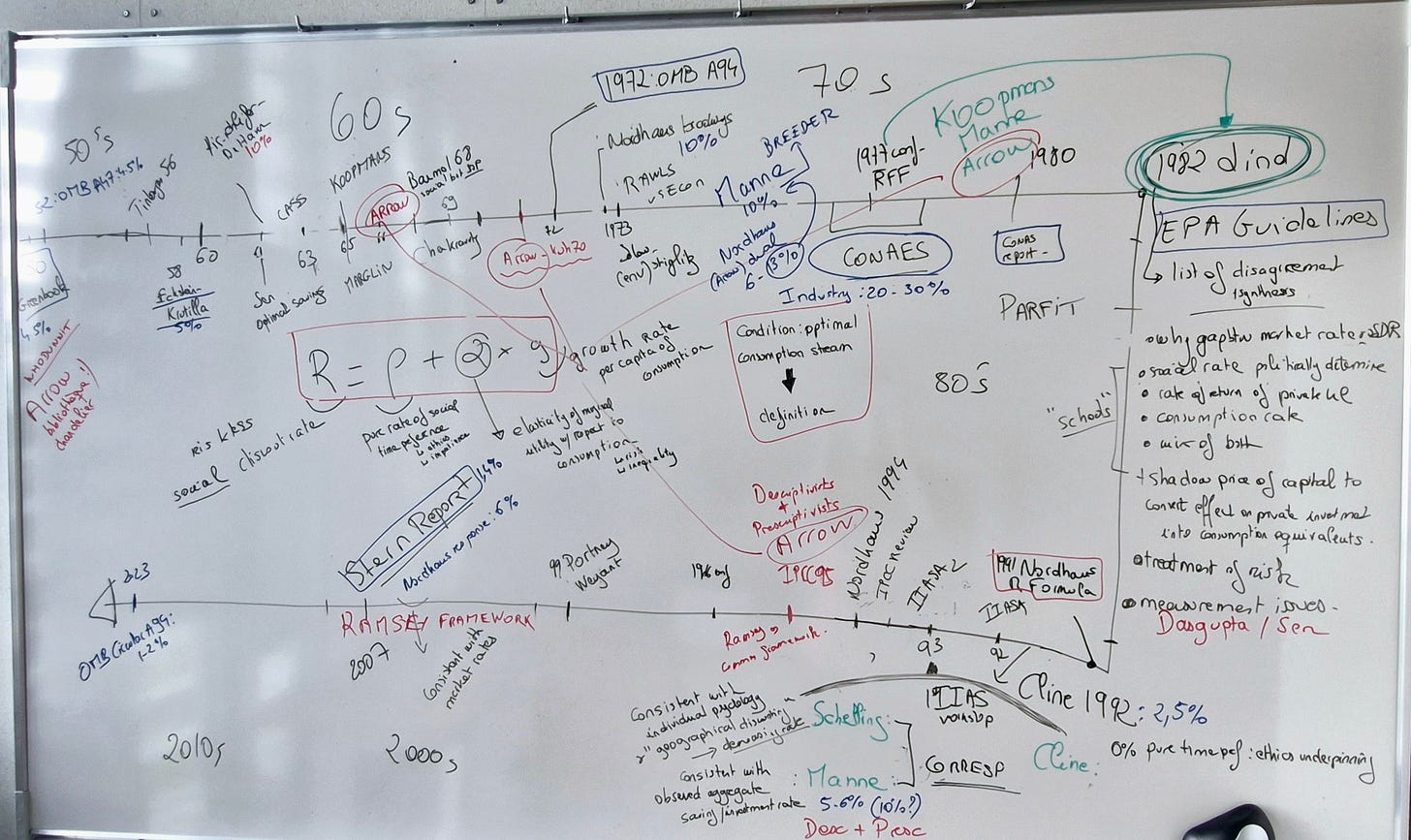

The featured picture is the chronology I spent a good chunk of winter and spring skteching on my whiteboard, adding bells and whistles after each zoom with Pedro. We’re now in the final stages of trimming down the paper to put in online later this month, but I couldn’t get myself to erase it from my board today, before the break. The series took longer than I anticipated to complete, starting amidst the chaos created by the French snap election. Thanks for sticking with me (and I’m publishing the last episode, we still don’t have a prime minister and government anyway).

This research has got me wondering about the other techniques economists use beyond discounting to model the future. This, in turn, has led to some reflections with colleagues about the history of economists modeling the future (or choosing not to). So, there might be a season 2 in the works. If you have any key contributions, models, or techniques you think we should cover, I'd love to hear about them.