S1E6: “Ramsey does not believe in a time-discount rate bigger than zero; that makes three of us”

Ethics strikes back

This post is part of a series on the history of how economists model the future with the Ramsey formula, based on joint work with Pedro Garcia Duarte. See episode 1 , episode 2, episode 3, episode 4, episode 5. Full Paper here

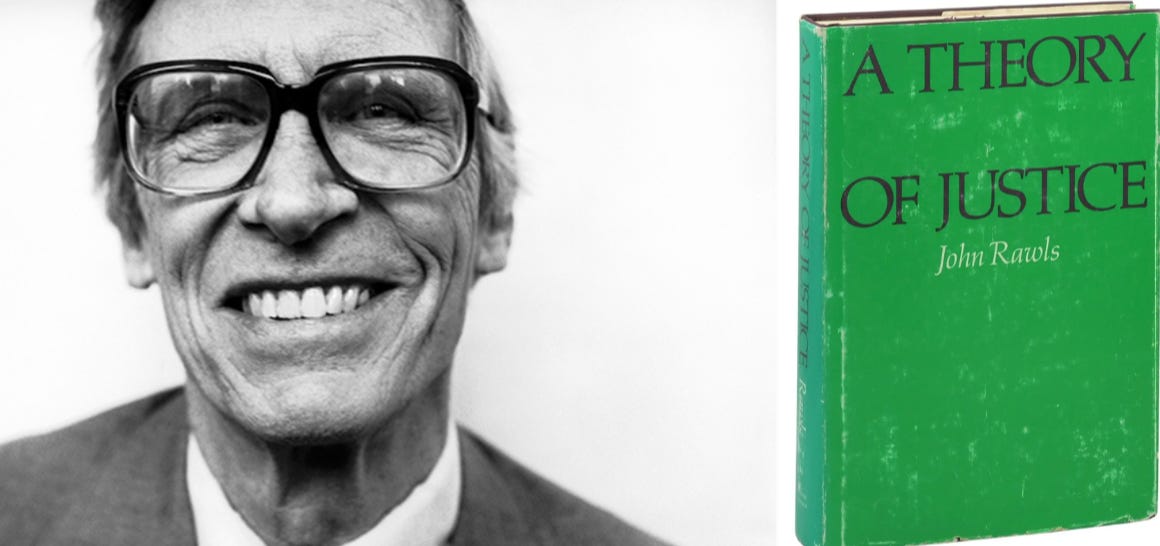

Economists’ growing concern with discounting for the “distant” future wasn’t just about natural resources running out, the energy crisis, or general future-angst. It was also sparked by an unlikely character, a philosopher. In 1971, John Rawls dropped A Theory of Justice, a book that was part inspired by, part written against, and definitely meant for economists. Rawls intended to offer an alternative to the utilitarianism that infused economic theory. He famously proposed that, placed under a veil of ignorance about their circumstances, citizens would choose a system that, first, guarantees basic freedom, and second, ensures fair equality of opportunity and only allows inequalities that benefit the worst off (the difference principle, which economists dubbed the maximin).

Rawls made it clear that the difference principle should only apply to justice within generations (“there is no way for later generations to improve the situation of the least fortunate first generation”). But then, how to deal with “the problem of justice between generations”? He devoted two chapters to the issue. His idea was that “each generation must not only preserve the gains of culture and civilization, and maintain intact those just institutions that have been established, but it must also put aside in each period of time a suitable amount of real capital accumulation.”

Rawls knew he was treading on economist turf here. Citing Sen, Koopmans, Solow, Ramsey and Chakravarty, he called his vague substitute for the difference principle the “just saving principle.” He also recognized that economists had long connected savings, growth and intergenerational justice with discounting. His take on it was a bit fuzzy: he reminded readers that there was no moral ground for discounting, but also admitted that the “utilitarian principle may lead to an extremely high rate of saving which imposes excessive hardships on earlier generations.” He concluded that this “can be to some degree corrected by discounting the welfare of those living in the future.”

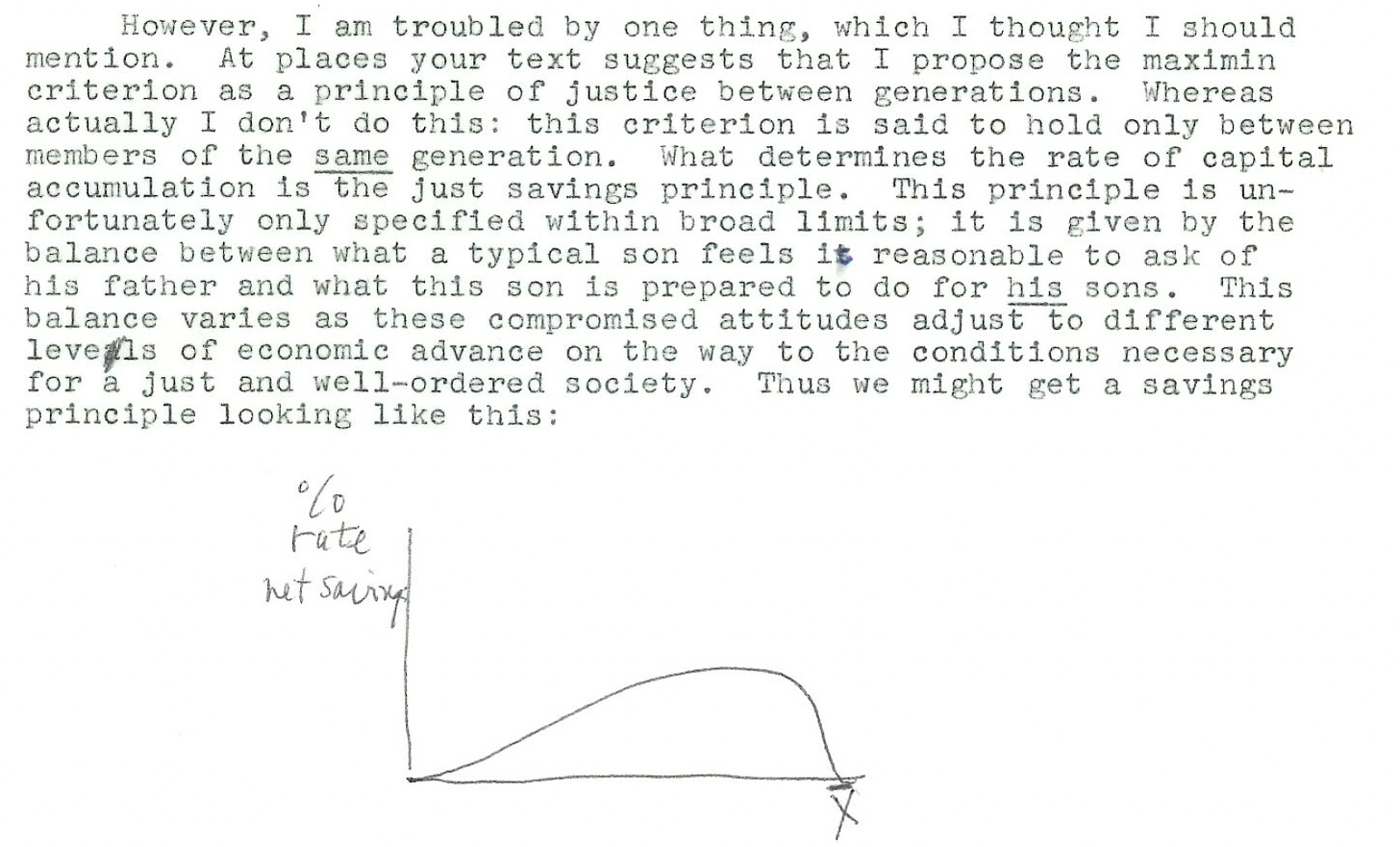

Naturally, the economists we've met in previous episodes couldn't resist responding to Rawls. Solow sent him a draft of his 1974 article on “Intergenerational Equity and Exhaustible Resources,” aiming to apply the maximin principle to intergenerational equity and optimal capital accumulation. Rawls pushed back, reaffirming that his principle was not to be applied between generation, and should be replaced with the just saving principle:

Unfazed, Solow doubled down, and, in the published paper, declared to be “plus Rawlsien que le Rawls” (sic, French reader). Arrow proposed his own intergenerational difference principle, while Dasgupta interpreted of the just saving principle as a Nash equilibrium game between generations. Rawls liked the latter interpretation better: “I…imagine…that one tries to ascertain at each stage of accumulation how much one would be willing to save for one's immediate descendants by balancing that against what one feels entitled to claim of one's immediate predecessors….Therefore your Nash equilibrium reading of the savings principle is certainly justified.”

Discounting popped up in these exchanges too, with the usual ambiguities. Solow told Rawls “Ramsey does not believe in a time-discount rate bigger than zero; that makes three of us, including you and me.” But he quickly added that the real issue was figuring out whom the utility function belongs: a “representative individual” or “each and every individual” or “the decision maker” were all fine: “the choice of a social discount rate (which we prefer to be zero) and a social valuation of consumption at different points of time and of different amounts is what has to be done to formulate a well-posed problem about optimal saving,” he concluded. In his 1974 article on the maximin and exhaustible resources, he therefore chose not discount. But as he was discussing with Rawls, Solow also attended the Brookings panel where Nordhaus grappled with discounting (see previous episode). He commented that “even with a utility discount rate of zero, the consumption rate of discount would be positive if per capita incomes are expected to be higher in the future, because of the diminishing marginal utility of income. I do not know if 10% is exactly the right rate of discount; but I would not use a very different number.”

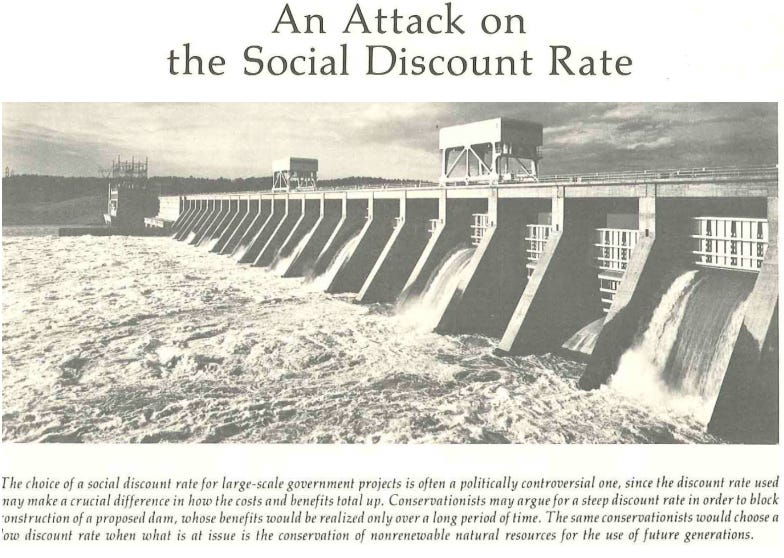

The exchanges between Rawls and economists on intergenerational justice and discounting wasn’t a one-off thing. Soon after political philosophers, moral philosophers joined the party. At the turn of the 1980s, Gregory Kavka, Mary B. Williams and other contributors to a book on obligations towards future generations, John Broome (also an economist), and Derek Parfit weighted in on discounting – the latter trying to combine his long-term interest in identity across time with a concern for future generations and pressing issues of energy policy, quickly launching “an attack on the social discount rate” on the way. Aside from the economic arguments for or against discounting that gradually became embedded in the Ramsey formula (people will be richer tomorrow, exhibit inequality aversion; less likely events require discounting), these philosophers proposed new arguments against it. They asked tricky questions: should our attitudes toward future generations reflect our moral obligations to strangers? Do we have more responsibilities towards people in the near future? Should we use the same discount rate for all effects? Does uncertainty over the future mean that moral priority should be given to living individuals?

Over time, a general impression formed that economists were pro-discounting while philosophers were against it. This relied on an ambiguity on which discount rate is debated (the pure rate of time preference or the social discount rate), and on which type of argument was made: ethical, on tractability, or axiomatic (for instance on properties of the social welfare function)? There has recently been a convergence between the 2 groups on numbers, though not on underlying rationales.

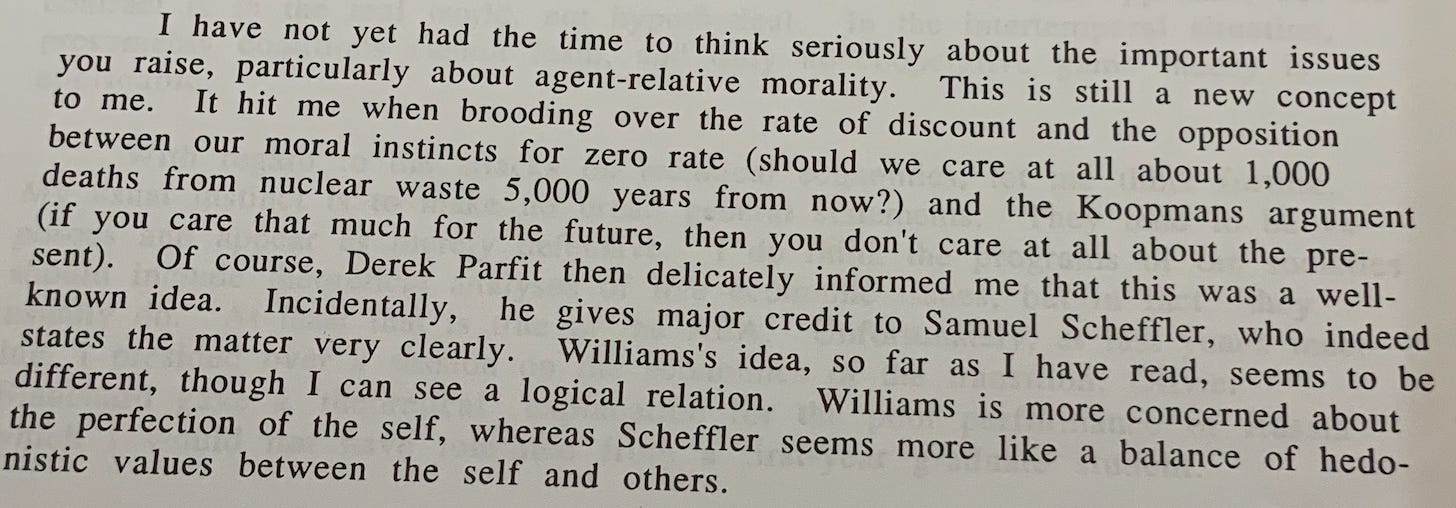

From the 1970s onwards, then, the ethical arguments for/against discounting got more explicitly articulated and combined with theoretical and tractability ones. Whether these new voices swayed some economists is well beyond the scope of our research. It requires pinning down epistemological differences between philosophers and economists. But this 1997 letter by Arrow highlights how economists’ reflections were permeated by philosophical arguments:

“Ethics are agent-relative in the crude form that my obligations are a mixture of the personal self-interest (including William’s perfectionism) and moral obligation (this is more or less Scheffler’s formulation),” Arrow concluded.

At this point, neither these ethical discussions nor their framing into the Ramsey formula were central to the "consensus" on discounting that emerged in the early 1980s. But they were definitely stirring the pot, setting the stage for future debates

Next S1E7. Not “operational”: a consensus without the Ramsey Formula

I love the idea of Rawls in conversation with economists, I had no idea. Thank you!

Fascinating, thanks for this very interesting piece.