This post is part of a series on the history of how economists model the future with the Ramsey formula, based on joint work with Pedro Garcia Duarte. See episode 1 , episode 2 and episode 3. Full Paper here

In the previous posts, I outlined two groups grappling with discount rate selection in the1950s and 1960s. First, the microeconomists and applied welfare theorists analyzing the costs and benefits of water infrastructure, then other public investments. Second, the growth theorists who sought to reframe Ramsey’s theory of optimal savings using optimal control tools. This was not solely an American story. With just a few months delay, young UK-based growth theorists warmed up to Pontryagin’s charms, which Hiro Uzawa carried in his suitcase upon visiting Cambridge and Oxford in 1966-67. But initially, their focus wasn’t on determining social or consumption discounting rates or improving cost-benefit analysis.

One important exception was Kenneth Arrow. Any one-sentence summary of his archivements by age 44, when he enter our narrative, seems overwhelming. We encounter him after two decades of work on uncertainty and risk in market equilibria, on bringing mathematical programming to economics, having just completed a contribution to the theory of what was not yet called endogenous growth, and an exploration of the implications of information market failures on medical insurance, while obsessing over optimal policy and resource allocation theory. This wealth of knowledge informed his approach when Kennedy’s Council of Economic Advisors asked him to discuss investment in public goods, including discount rate selection. Shortly thereafter, he participated in a Resource for the Future conference on Water Resource Management. He chose to address discounting in public investment directly.

In just 3 introductory pages, Arrow argued that (1) that capital market imperfections alone justify dismissing the use of market rates (he briefly mentioned a “special collective responsibility for future generations”) and (2) since “public investment policy by definition involves commitment over time, as modern economic theory makes clear, [it] must be judged in the context of a growing economy.” He contended that choosing a discount rate for "optimal policy" required using an optimal growth framework allowing for reinvestment. He then outlined a model with private and public capital, drawing on Ramsey's 1928 work. Without going into technical analysis, demonstrated the gap between this Ramsey benchmark and reality created by market imperfections.

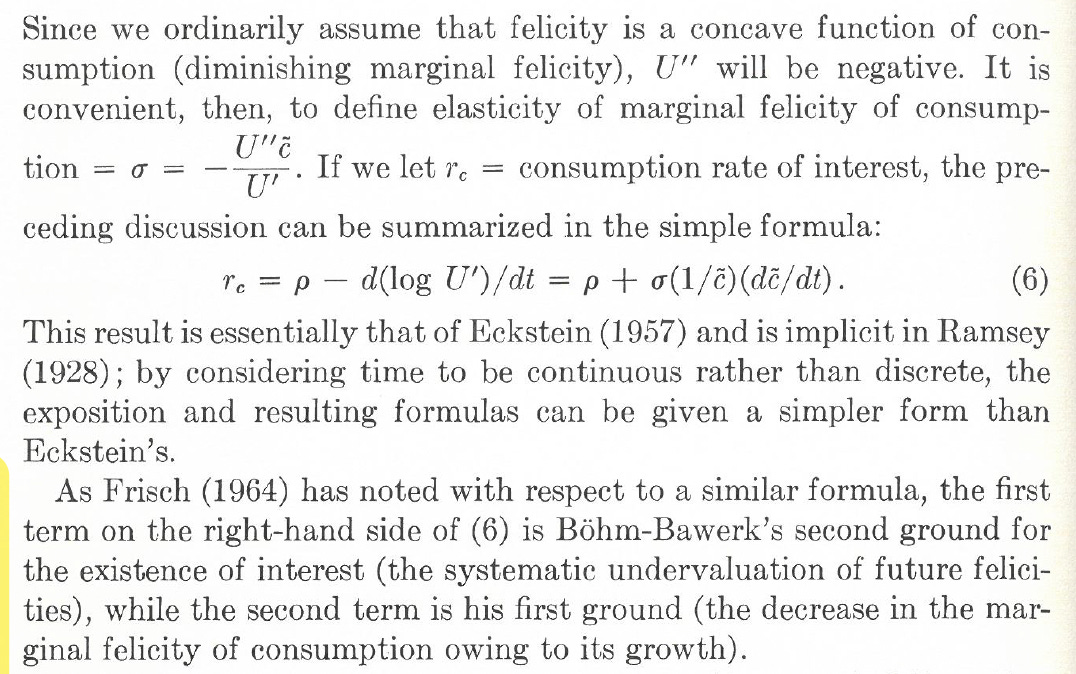

After RFF gave him a grant to pursue this work, Arrow asked his fellow Stanford theorist Mordecai Kurz to collaborate with him on a series of papers, culminating in their 1970 book Public Investment, the rate of return, and political fiscal policy. A student of Arthur Okun and Ed Phelps at Yale, Kurz was one of the earliest adopters of Pontryagin’s maximum principle. Though not specifically interested in discounting, but as he joined Stanford full time around 1966, he was deeply involved in defining optimal investment rules for public goods. Their 1970 book w various audiences. It was primarily written for academic specialists but through an introductory informal summary and an introduction to optimal control theory, the authors also hoped to draw the attention of cost-benefit practioners.

They framed the book as a theory of economic policy in the tradition of Tinbergen, but set in a dynamic context and centering on market imperfect (credit rationing, the lack of forward markets etc). Their justification for discounting reflected the usual blend of theoretical, ethical and tractability concerns. They first clarified that any choice of objective function was subjective and explained that they had settled on one (the now-accepted intertemporal maximization of discounted utility) that was “analytically manageable” and reflected “value judgments.” They defended discounting as consistent with individual choice theory, countering Ramsey’s 1928 famous quote against discounting ethics with an earlier pro-discounting statement the later had offer in an Apostles talk (the Cambridge male only secretive debating society), and conluded with Koopman’s theoretical arguments.

Arrow and Kurz then presented a simple Ramsey-inspired growth model. They explicitly derived a relationship between the consumption discount factor, the pure rate of time preference and the marginal utility of consumption, which they relate to Eckstein, Eugene Böhm-Bawerk and explained was “implicit in Ramsey (1928).”

On the optimal path, it equals the marginal productivity of capital, eliminating the need to choose between the cost of capital and social discount rate approaches. As typical with Arrow, the exercise was meant to provide a benchmark for exploring “the dark jungles of the second best” (an expression I borrow from William Baumol). In the next chapters, they lengthy examined how these rates diverge with public goods, risky investments, increasing returns to scale, and various public investment financing schemes (income, consumption, savings and wage taxes, and debt). Kurz went on to study other topics, but not before attempting to measure individual discount rates through survey methods (yielding results from 30% to 150% annually!). For Arrow, however, this five-year work establishing a theoretical framework on “the determination of the rate of interest appropriate for making investment decisions” was just the beginning.

At the turn of the 1970s, then, an equation determining the rate of interest on the optimal growth path was thus circulating among economic theorists. Not yet a rule or formula, it was variously associated with Ramsey’s name, but did not reflect how cost-benefit analysis specialists picked discount rates for public investment decisions. It might had remained obscure to the latter, had the economic, social and intellectual landscape not dramatically shifted in the next 3 years: the energy crisis, the publication of the Meadows report and associated debate on the role of exhaustible natural resources in growth, and 20th century’s most important political philosopher knocking at economists’ door all demanded urgent clarification of discounting practices. But how so?

Next (S1E5) “Proof for a case where discounting advances the doomsday” : discounting in 1970s energy models