This post is part of a series on the history of how economists model the future with the Ramsey formula, based on joint work with Pedro Garcia Duarte. See episode 1 , episode 2, episode 3, episode 4, episode 5, episode 6, episode 7. Full Paper here

The “Lind consensus” that I described in my previous post turned out to be short-lived. Built around energy debates, it felt apart in less than a decade as economists’ focus shifted from exhaustible resources to global warming. Evidence of Co2 emissions raising global temperatures had been piling up since the 1960s. In response, the United Nations set up the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (hereafter IPCC) in 1988. Tasked with summing up what scientists knew about climate change, it produced a first report in 1992. It covered research on emissions and temperature effects (Working Group I), ecosystem impacts (Working Group II) and future emission scenarios (Working Group III). Sensing the growing importance of economics in climate research, IPCC leaders reoriented the third working group for its the second assessment. The new focus was on conducting “technical assessments of the socioeconomics of impacts, adaptation, and mitigation of climate change over both the short and long term and at the regional and global levels.”

While today’s discussions often point to a lack of mainstream economists’ involvement in IPCC reports, the early round heavily relied on them. The team determining the scope of the second assessment included Joseph Stiglitz, who gathered a large cast of economists from developed and developing countries -many names you might recognize from the previous episodes.

The final report of Working Group III, dated 1995 but published 1996, featured a whole chapter on “Intertemporal Equity, Discounting and Economic Efficiency.” It was presented alongside other chapters on decision-making, equity, the principles of cost-benefit analysis, and integrated assessment of climate change and mitigation strategies. The writing team included Arrow; William Cline, who had just published a book on global warming advocating for a 300-year time horizon, discount rates in the 1-2% range, and quick and substantial greenhouse gas abatement path (more in the next post); Karl-Göran Mäler, a Swedish environmental economist who had just founded the Beijer Institute for Ecological Economics with Dasgupta; Sri-Lankan economist Moran Munasinghe from the World Bank, Stiglitz; and US Treasury staff member Ray Squittieri.

The chapter was influential for 3 reasons: first, it marked the end of the Lind consensus by highlighting disagreements is discounting approaches. Second, it proposed a widely adopted dichotomy to characterize these disagreements: the “prescriptive” approach, which “begins with ethical considerations” was “usually associated with a relatively low discount rate.” The descriptive approach “focuses on the (risk-adjusted) opportunity cost of capital” and “begins with evidence from decisions that people and governments actually make.” Third, it established an equation as the agreed “general framework” in which “the discount rate can be expressed...It provides a way to think about discounting that subsumes many related subtopics, including treatment of risk, valuing of nonmarket goods, and treatment of intergenerational equity.”

It wasn’t called the Ramsey formula, but it was used throughout the chapter to explain the prescriptive approach (in which the equation defines the social rate of time preference), while implying that, in the descriptive approach, it would equal the cost of capital. The long appendix built on Arrow-Kurz and Koopmans to derive the discount rate for the time path of consumption from a social welfare function, and introduced the “Ramsey rule,” whereby the discount rate equals the productivity of capital on the optimum path. It then extensively covered debates on consumption vs investment discounting, Rawlsian criteria, risk, declining discount rates (“empathetic distance”), and the relationships between notions of intergenerational equity and “sustainable development.”

Interestingly, the archival record reveals that this chapter underwent dramatic transformations during its two-year writing process. Initially, it wasn’t even part of the plan for the IPCC report – you might expect that discussions of intergenerational justice could have been included in the chapters on decision-making, equity and social considerations or cost-benefit for climate change. As Arrow joined the writing team for another chapter mid-1993, he wrote to the coordinator:

“your outline is very complete, with one exception. There needs to be discussion of discount rates. To a considerable extent, suggested policies require present costs (reduced carbon consumption) to prevent future disutilities and costs. Clearly, the tradeoff between present and future is very important, controversial though it be.”

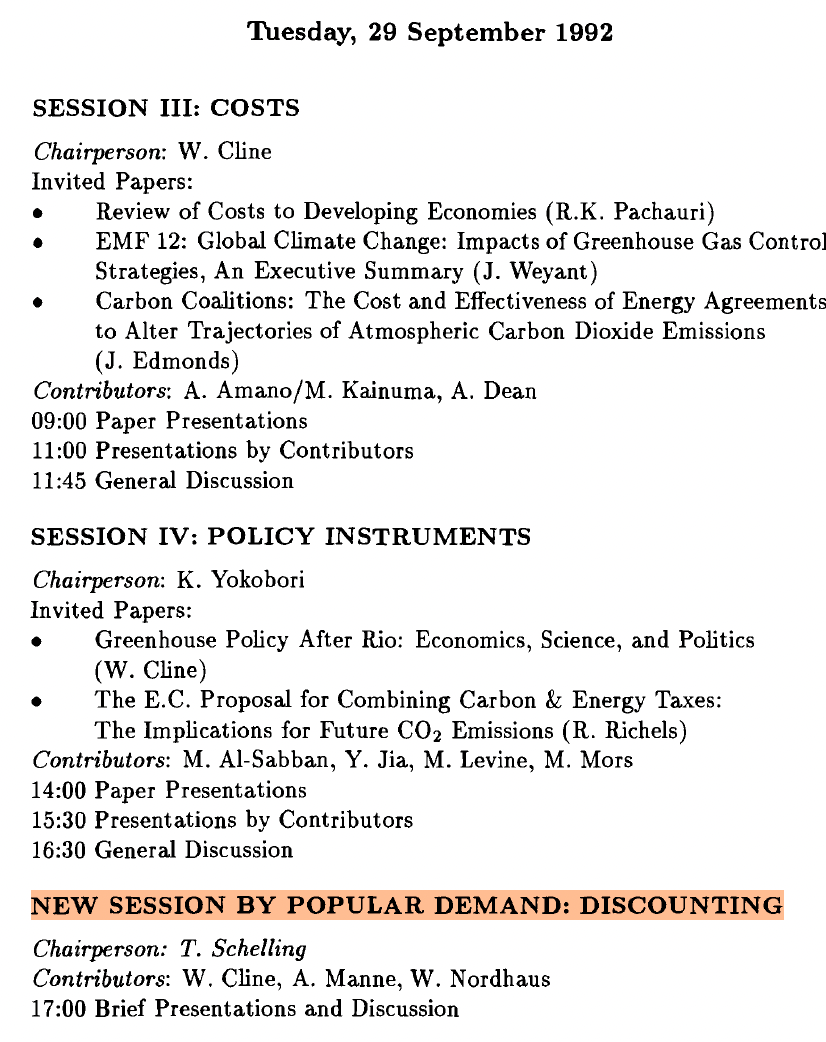

Arrow’s request echoed a larger conversation that had kicked off a few months earlier, during the first of a series of workshops organized jointly by the Energy and Industry subgroup of the IPCC and IIASA. Sponsored by institutes from the US, Europe and Asia, there meetings were where the regional and global models for IPCC integrated assessment of carbon mitigation strategies were debated. At the October 1992 workshop, a “new session by popular demand” on discounting was added late in the program, without prepared papers.

These disagreements were so intense that even Swedish meteorologist Bert Bolin, the first IPCC head, mentioned them in the memoir of his 10-year tenure. “Heated debates arose in considering the issue of equity…between generations,” he recalled. He explained that discounting was the “principal analytical tool” economists use to deal with intergenerational equity and quoted the 1996 report’s conclusion that “how best to choose a discount rate is, and will likely remain, an unresolved question in economics.”

The writing team was thus assembled with contributors to other framing chapters. The first draft they sent around in the Fall of 1994 differed markedly from the published version. Most of the material that ended up in the appendix was featured in the main text, which was entirely built around the notion that economists were moving “Toward an emerging consensus.” The authors floated a “widespread (but not universal) agreement” that “differences in overall standards of living should be reflected in the discount rate,” and regarding “the inadequacy of simply adopting market rates.” They quickly set aside the cost of opportunity approach and presented a Ramsey formula unambiguously defining the Social Rate of Time Preference.

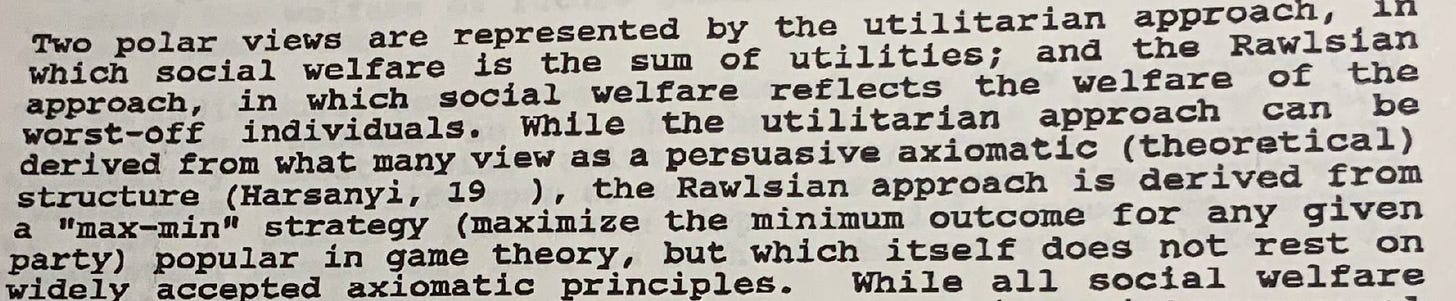

They then moved to long discussions of intergenerational equity, comparing utilitarian and Rawlsian approaches. They clarified that arguments for or against zero pure time preference weren’t just ethical or theoretical, but also reflected tractability constraints.

The divides were between philosophical approaches, not economic ones. The terms “prescriptive” and “descriptive” were nowhere to be seen.

So it seems that the rise of climate modeling, mediated by the early IPCC assessments, acted as a catalyst. It led to a convergence on using the Ramsey formula to define the discount rate, but also sparked disagreement on how to parameterize it. But what or who exactly drove these IPCC economists to shift from pushing a consensus to acknowledging a rift between descriptivists and prescriptivists in less than two years? As is often the case in the history of recent economics, this is a “referee 2” story.

Next S1E9. “The paper is based on a prescriptive rather that descriptive view of political economy”: one equation, two approaches