What is the social responsibility of business: from Friedman’s ideas to “the Friedman doctrine”

Histories of Corporate Social Responsibility, part 1

Stop blaming Milton Friedman?

This post belongs to a series exploring how economists have historically approached Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR). This is research very much in progress, aimed at fostering conversations with CSR researchers across economics, management, and law, while helping me develop lectures on the intersection of economic history and business. I've been teaching about economists who shaped—and were shaped by—20th-century public policy. But I've grown increasingly frustrated at my inability to offer a parallel lecture on the private sector. There's much less work on how economists have conceived the firm theoretically, studied business practices empirically, and shaped them through advising. This gap exists mainly because we have far fewer sources available compared to public policy research.

Researching economists' historical approach to CSR essentially means examining how they've answered a fundamental question: What is or should be the corporation's primary goal? In whose interests should corporations operate? To whom are they legally accountable? Or, in economic terms, what's the firm's objective function? These multiple, overlapping formulations reveal the ambiguities that run throughout this story: twin questions—some positive (about what is), others normative (about should be). Twin vocabularies: some straightforwardly "economish," the type found in industrial organization papers in academic journals; others drawing from the language used by economists in business schools, management scholars, and practicing managers; and still others employed by corporate law scholars interested in what the "corporation" fundamentally represents—whether it serves shareholders, managers, stakeholders; whether it exists as an independent legal entity.

Histories of CSR in the 20th century abound, but these are mostly written by historians of management and corporate law scholars. When these accounts feature economists, they either focus on an era before economics and management had separated as disciplines (like the 1930s Berle-Means versus Dodd debate) or on later economists housed in business schools that, as Rakesh Khurana and Marion Fourcade observed, had restructured themselves along the lines of economics departments, once again blurring disciplinary boundaries (think Carroll, Jones, Freeman, Porter). The rise of finance as an intermediary field adds further complexity. These historical narratives nevertheless reflect their authors' disciplinary backgrounds. Most management scholars present an inexorable, continuous rise of CSR scholarship, chronicling the successive emergence of stakeholder theory, sustainable development, strategic CSR, shared value, and ESG investing. Finance specialists, by contrast, emphasize the ascendancy of shareholder primacy. My goal is to understand what a distinctly economics-oriented narrative might look like.

A few longer historical perspectives have emerged in recent years. The volume edited by David Chan Smith and William Pettigrew traces business-society relationships back to America's emerging non-profit sector, the Muscovy Company of 1555 (England's first joint-stock company), medieval uses of the term "corporate," and even the Code of Hammurabi. David Gindis's special issue examines the English East India Company and its merchant guild predecessor the Levant Company in the 1600s, traces limited liability concepts from the 17th century, and analyzes Ernst Freund's work on corporations' legal nature."

Whatever their disciplinary, geographical, or historical scope, all existing histories of corporate social responsibility share one thing in common: Milton Friedman's 1970 New York Times piece, "The Social Responsibility of Business Is to Increase Its Profits." Super-titled "A Friedman Doctrine" likely by the Times editors, this article has been widely credited with reshaping a century-long debate over corporate purpose and spearheading the shareholder primacy movement. Wrongly so, as corporate law professor Brian Cheffins recently demonstrated—and I agree with his assessment (more on this below). See his piece "Stop Blaming Milton Friedman!" for a thorough review of how Friedman's article became canonized. The piece now appears to be Friedman's most cited work, with over 30,000 citations according to Google Scholar—slightly surpassing Capitalism and Freedom and cited three times more than the academic works that actually earned him fame: A Monetary History of the United States and his Nobel Prize-winning Theory of the Consumption Function.

The irony is striking! Friedman devoted exactly four pages to this topic in 1962 (in Capitalism and Freedom), four more in 1965 (in a National Review article), and four again in the New York Times [edit: David Gindis kindly points to me that he in fact wrote 2 other pieces in the early 1970s, one for a collective volume edited by Leonard Silk and another one for a bank journal. And he gave a few interviews]. In the 700-page memoir he penned with his wife and co-author, economist Rose Director Friedman, he allocated exactly two paragraphs to CSR, mentioning that he originally received $1,000 for the article and that "hardly a year goes by that we do not receive more than that for permission fees to reprint the article." That's roughly the same space Stanford historian Jennifer Burns devotes to the topic in her great recent intellectual biography of Friedman. Friedman's massive archives at Stanford's Hoover Institution contain just three folders on the subject—mostly correspondence with little-known businessmen between 1970 and 1994, yielding far less material than a single Newsweek column sometimes generated. Most of these folders contain data on corporate charities gathered by another researcher in the 1970s—a telling detail I'll return to in the next post. So it seems "The Friedman Doctrine" quickly developed a life far more tremendous and independent from Friedman's actual ideas about corporate social responsibility. But since it's become an obligatory reference point—if not the starting point—for anyone interested in economists' views on corporate purpose, and since it perfectly captures the shifting intellectual and political dynamics of its era, here are some thoughts on the piece, its meaning, contexts and legacy.

A ”stepping stone to socialism”

As Friedman himself noted, the 1970 NYT piece was essentially repeated arguments he'd made eight years earlier in Capitalism and Freedom. Indeed, he closed his piece by citing his own 1962 words: “there is one and only one social responsibility of business to use its resources and engage in activities designed to increase its profits so long as it stays within the rules of the game, which is to say, engages in open and free competition, without deception or fraud.” His argument against CSR targeted recent instances where the government had asked business for self-restraint (like Kennedy's anger over a price increase by US Steel) and what Friedman saw as a growing tendency among businessmen themselves to endorse the idea, for instance through charitable donations – “it prevents the individual stockholder from himself deciding how he should dispose of his funds.” Thes trends “undermine the very foundations of our free society,” he explained. Friedman had laid out his argument in a chapter otherwise devoted to monopoly, simply stating that monopoly’s existence, since it’s exempt from the discipline of competition “raises the issue of the “social responsibility’…of the monopolist.” Earlier in the book, he had explained that the rise of monopolistic situations didn’t merely result from businessmen’s behavior, but often stemmed from misguided public policies that granted monopoly power to large firms – not public monopoly itself but “the use of government to establish, support and enforce cartel and monopoly arrangements among private producers.”

Friedman returned to the topic in a 1965 National Review article that flagged CSR as a “subversive doctrine.” This time, his main target was President Johnson’s recent appeal to banks to show restraint in making loans to foreign borrowers to protect the balance of payment - itself reminiscent of previous calls to banks to restrict their credit to productive uses. His criticisms focused on the government’s silly move to request voluntary exercise of social responsibility from corporations rather than using coercive power (which he wouldn’t endorse either). In doing so, the government was dodging its responsibility and, at the same time, was unwilling to “let the price system work.” But Friedman also raised a new, more political argument: if businessmen (the “agents”) imposed sacrifices on the owners (the “principals”), they weren’t acting as businessmen but as “public servants”, despite not being selected “through an explicitly political process.” Thus CSR becomes a “stepping stone to socialism,” he concluded.

Both the context and content of Friedman's final piece are well known, embedded in the New York Times column's visuals featuring the main protagonists of "Campaign GM," backed by lawyer and consumer advocate Ralph Nader. In an attempt to make General Motors more "responsible" regarding pollution, road safety, and quality, Nader's group purchased twelve GM shares to attend the annual shareholder meeting. Among other reforms, they proposed establishing a shareholder committee for corporate social responsibility. In response, GM did appoint more diverse board members and began investing in social initiatives.

In his column, Friedman mentioned "the recent G.M. crusade" alongside many other examples he'd developed over the past decade. This time, the piece focused more thoroughly on the businessman or corporate executive than on government officials. As many have pointed out, Friedman wrongly claimed that executives are employed by shareholders and therefore should "conduct the business in accordance with their desires, which generally will be to make as much money as possible while conforming to the basic rules of the society." This time, he also elaborated on the political implications of asking corporate executives to pursue social goals, reprising his argument that in doing so, businessmen effectively raise and spend taxes. They thus become "simultaneously legislator, executive and jurist... a public employee, a civil servant." He added that "those who favor taxes and expenditures... have failed to persuade a majority of their fellow citizens to be of like mind and that they are seeking to attain by undemocratic procedures what they cannot attain by democratic procedures." He included his usual warning that a "free society" (which he meant as one organized through the price system) makes it hard for good people to do good but also for evil people to do evil. "The political principle that underlies the market mechanism is unanimity," he added, contrasting it with "conformity," the political principle that in his view underlies the political mechanism. Without using an expression that he made much use of in his other writings, he was rejecting the tyranny of the majority. "There are no 'social' values, no 'social' responsibilities in any sense other than the shared values and responsibilities of individuals," he concluded.

Among the many researchers who have surveyed Friedman's evolving writing on CSR, historian David Chan Smith compellingly recapitulates the sources of his monopoly and political arguments. He places Friedman's thinking in the context of rising big companies and monopolies, noting how scholars like Berle, Means, Dodd, and Bowen systematically observed that research questions about whom corporations should serve were inescapably tied to the growing size and market power of large corporations. CEOs themselves, from General Electric to Standard Oil and US Steel, were endorsing the CSR rationale. Chan Smith unpacks Friedman's fears—not just of government regulation but of possible convergence between government and business interests. Government might create monopolies, but Friedman was increasingly concerned that businessmen would submit to what Chan Smith calls "internal politicization" (the corporation becomes a government agent) and that businessmen might use CSR as cover for regulatory capture (Friedman's close friend and colleague George Stigler introduced the term in an article published the next year). Businessmen aren't just "short-sighted and muddle-headed" but, in using the "cloak" of CSR, engage in "hypocritical window dressing," even "fraud." In a letter to the vice president of the National Association of Manufacturers a few weeks after the Times publication, Friedman explained that he should have emphasized more that "when it professes to be spending money in the name of social responsibility, [business] is in fact proclaiming that it has a monopoly position."

Friedman’s ambiguities are a feature, not a bug

The problem with interpreting the New York Times piece, though, is that Friedman proposed so many half-baked examples and lines of argument that you can rightfully pull any of the many sometimes inconsistent threads. This shows up prominently in the set of essays gathered on the ProMarket website for the 50th anniversary of Friedman's Times piece. Chicago economist Luigi Zingales proposed turning the Friedman doctrine into a "Friedman Separation Theorem." It states that under certain conditions—competitive environment, no externalities, complete contracts—it's socially efficient for managers to maximize what has since become "shareholder value." Since these conditions don't hold, he argued (along with Olivier Hart), the appropriate objective function for a firm should be to maximize shareholder welfare. Finance professor Alex Edmans focused on the underlying lack of comparative advantage embedded in Friedman's insistence that the value of expenditures must be measured "on a dollar for dollar basis." Law professor Margaret Blair, among others, focused on the shaky legal foundations of Friedman's piece.

An important aspect that scholars have overlooked is how much Friedman's three CSR pieces (1962-1970) actually focus on macroeconomic stabilization rather than corporate governance per se. Friedman's concern wasn't just with attacks on the market system but with statecraft at large. And it derived as much from the concerns of the day as from Friedman's longstanding research: if there's a doctrine he was trying to sell in these years, it was monetarism. 1962 was the publication year of his and Anna Schwartz's two decades of careful collection of money supply data and analysis, The Monetary History of the United States. He had published earlier with Stigler on price ceilings. His main Capitalism and Freedom example against CSR dealt with government exhortations that businesses "keep prices and wage rates down in order to avoid inflation." His main 1965 target was Johnson's message that banks should adapt their lending policies and, again, "the guideposts of the Council of Economic Advisors" on wages and prices. 1965 was the year British Conservative politician Iain Macleod coined the term "stagflation" during a speech to the House of Commons. The corporate executive "is told that he must contribute to fighting inflation," Friedman complained in the 1970 piece, alongside denouncing a new call to fight "pollution," a term Friedman returned to several times. His column appeared five months after the first Earth Day (April 1970), and just as environmental concerns were gaining momentum—two years before the OECD adopted the polluter-pays principle and economists began debating the Club of Rome report.

Overall, Friedman's goal wasn't so much to participate in a debate over corporate governance or what the firm's goal should be. The 1970 piece was a combined set of arguments to protect free markets from various threats. It wasn't meant as a theorem, not even a doctrine as the Times supertitle suggests. Furthermore, the many ambiguities in the Times piece aren't a bug—they're a feature. The think piece fought several evils at once (pressures, campaigns, and regulations on charities, pollution, macroeconomic stabilization, and more), weaving together ethical, legal, political, and efficiency arguments in a packed argument that Friedman never returned to. It wasn't the first time he employed this strategy. Friedman's only epistemology publication, "The Methodology of Positive Economics" (1953), was, by his later admission, framed with exactly the same strategy: it fought many evils at once (the Cowles Commission's charge of "Measurement without Theory," monopolistic competition, opponents to marginal cost pricing) with arguments that derived some of their huge appeal from their ambiguity (the "as if" methodology and the statement that a model's success should be judged by its predictive rather than explanatory power). Yet Friedman never provided additional explanation or agreed to discuss it on purpose. Asked by historians and philosophers to respond to a series of comments for the 50th anniversary of the essay, he refused and explained: "I have myself added to the confusion by early adopting a policy of not replying to critiques of the articles... That act of self-denial has quite unintentionally been a plus for the discussion of methodology. It has left the field open for all comers." Just like the Times piece, it shaped readers' epistemological approach to models and realism for decades. And just like the Times piece’s title, it eventually evolved into a pop version (the "as if" statement) rather independent of the original writing. Both became slogans, magic formulas of their own that economists and commentators sought to use or condemn as weapons or curses (Expelliamus!)

From normative political stance to positive economic research on CSR

The comparison with the 1953 essay also highlights an important tension in Friedman's writing on CSR and comments about it. The 1953 article concerns the methodology of positive economics. Friedman's few CSR writings, however, are purely normative. These aren't concerned with whether firms do maximize profits, but whether they should. And though normative economics was then a lively and prestigious field (with sharp ongoing battles over the definition of a welfare function by Arrow and Samuelson, Sen challenging the informational basis of ordinal utility functions, etc.), Friedman didn't follow this line—he went straight into discussing the risks and benefits of alternative political structures. His pieces aren't the product of a scientist but of a political thinker. As I have argued years ago, Friedman has always considered that the overall consistency of his political and scientific views on markets was a matter of “luck.” On monopolies, however, his “schizophrenia” created tensions. On the one hand, Friedman-the-political-thinker warned that large corporations endorsing CSR posed a threat to free society. On the other hand, Friedman-the-scientist constantly argued that the importance of monopolies in the US economy was greatly overestimated—in line with his own observations about the gap between the US and Europe, as well as empirical studies by Warren Nutter and other participants in Aaron Director's Free Market Studies.

Moreover, the 1953 article was primarily written as a response to economists debating precisely whether they should write models assuming that firms maximize profit. The goal here isn't to revisit what has been called the "marginal cost controversy" of the 1940s, which pitted proponents of monopolistic and imperfect competition against those advocating marginal cost hypotheses. Much has been written on this (see in particular Roger Backhouse’s article). My claim is that focusing too exclusively on Friedman's piece has overshadowed the positive line of work that most economists were pursuing in these postwar decades on how to model firms' behavior and goals. This history is partly theoretical, partly about tools as well. The 1940s controversy wasn't just about hypotheses—it was also very much about using questionnaires to understand how businessmen set wages and prices and what goals they had in mind. The next post examines some of this research, from Baumol's managerial theory of the firm to Arrow's writings about CSR, early behavioral economists' work, and how charitable giving shaped economists' understanding of corporate goals.

Looking beyond the trigger

Before I get there, let me close this already too-long post with the question of Friedman's legacy. Did his 1970 New York Times piece become an instant hit? Yes, of course—Friedman's writing, just like Krugman's today, has that power. Though there's not yet a systematic bibliometric, network, and word-embedding study of its reception, a qualitative study of citations to his work up to the 1980s shows that it was immediately taken up in business and academic settings.

Was it instantly cited because it was new? No, it recapitulated an old line of thinking that Friedman himself attributed to no less than Adam Smith. Was it because it convinced people? Just the contrary. As Brian Cheffins explained, interpreting Friedman's 1970 piece as launching the "shareholder primacy" movement gets both the post-Friedman chronology wrong and, as I will argue next, the pre-Friedman one too (shareholder/stakeholder are terms that Friedman never used). Cheffins, among other historians, argues that the business turn to shareholder primacy took place two decades later. Like many other CSR writers, he uses the statements of the Business Roundtable, a gathering of CEOs from major US companies. In 1981, their "statement on corporate responsibility" explained that "managers are expected to serve the public interest as well as private profit." In 1990, the orientation still was "to carefully weigh the interests of all stakeholders as part of their responsibility to the corporation or to the long-term interests of its shareholders," reflecting management research showing that the interests of shareholders and stakeholders were not only difficult to disentangle but also consistent with one another in the long term. The tone only changed in 1997: "the paramount duty of management and of boards of directors is to the corporation's stockholders... the notion that the board must somehow balance the interest of other stakeholders fundamentally misconstrues the role of directors." The next shift would occur in the 2019 statement, which began by stressing "a fundamental commitment to all of our stakeholders."

This is consistent with both quantitative and qualitative evidence offered by Marion Fourcade and Rakesh Khurana. They show that the notion of "shareholder value" strongly picks up both in academic publications and newspapers such as the Wall Street Journal, the Financial Times, and the New York Times beginning in the early 1990s—twenty years after Friedman's piece.

To anticipate the next post, the chronology is thus: up to the 1930s, the default idea was that corporate executives should maximize profit. In 1931, lawyer and New Deal architect Adolf Berle (of Berle-Means separation-of-ownership-and-control fame) argued in the Harvard Law Review that corporate powers should be used "only for the... benefit of all the shareholders as opposed to being left to director discretion." He feared that with the growing size of US corporations, managers would become an oligarchy of their own. Law professor Merrick Dodd countered that it was "undesirable... to give increased emphasis at the present time to the view that business corporations exist for the sole purpose of making profits for their stockholders." A debate ensued. By 1954, Berle conceded that "events and the corporate world pragmatically settled the argument in favor of Professor Dodd." By the 1970s, most law, finance, and economics scholars were studying or arguing in favor of CSR. Nader and his Raiders dominated a public debate marked by business scandals, growing distrust toward giant corporations, and a flow of consumer and environmental regulations. The government was even considering using federal charters—the legal contract between corporations and the state—to redefine business-society relationships. To explore this possibility, Congress held hearings on Corporate Rights and Responsibilities in 1976.

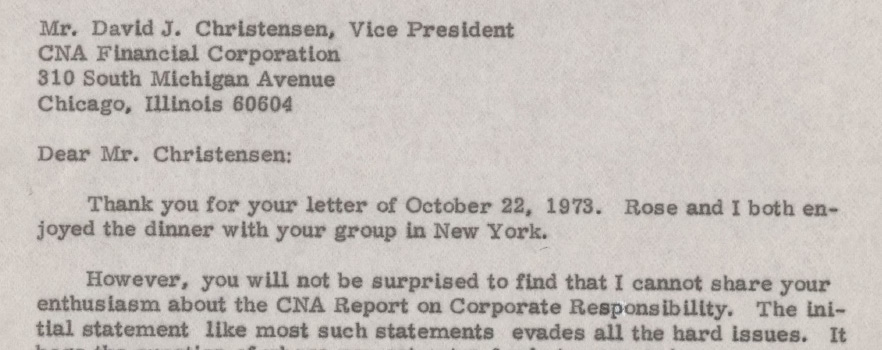

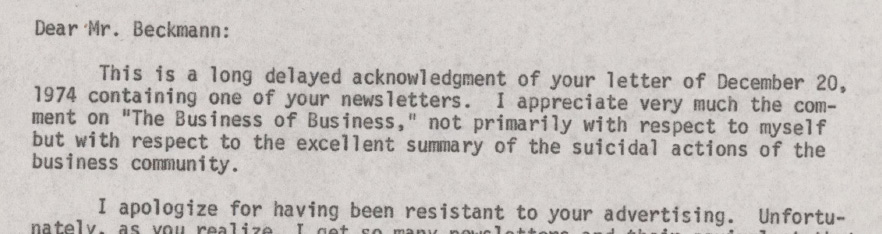

Why the tide turned in the 1980s is another topic. Cheffins points to the wave of corporate takeovers and new valuation methods in trading rooms. Fourcade and Khurana trace how Michael Jensen brought his ideas from Rochester to Harvard, where he established influential courses on corporate finance. But what is clear is that Friedman's column was thus, as often, a resistance piece—one that didn't change minds. The correspondence he received in response to the piece over the next decade was mostly from businessmen: the VP of the National Association of Manufacturers, the VP of CNA Financial Corporation, the PR director of Arthur D. Little. All of them disagreed with Friedman and offered rationales for why their firms should pursue social goals.

In 1998, Friedman reflected that the piece

"has become a standard item in business and law school courses on ethics. Teachers want to assign readings on 'both sides.' Few other economists have been willing to take so extreme (I would say, straightforward) a position, hence my article is in demand to present a defense of what most of the instructors doubtless regard as an indefensible position."

As David Gindis demonstrated in an excellent article, the most vocal CSR critic was actually Henry Manne—a legal scholar who helped organize the law-and-economics movement—rather than Friedman. Manne spent most of the 1970s making largely unheeded arguments against corporate social responsibility. Friedman's piece is important historically not because it not because it changed minds, but because it became a cultural touchstone. It was a "trigger"—and as Gindis reminds us, that was the term Jensen remembered Karl Brunner using when, a couple of years later, he asked Michael Jensen and Rochester colleague William Meckling to write a paper along Friedman's lines. But that's a story for a third post.