It’s still not clear to me what substacks are for. I thought that my next post was going to be about Ed Prescott’s work. But I’ve been trying to finish an article lately, and I’m stuck. So why not make this letter a space to reflect on my failures. And one to complain, because I love complaining. This article is one on the history of urban economics that I’ve been writing with Anthony Rebours for years. I tweeted about it, and we wrote a blog post summarizing the main storyline two years ago. The network analysis has since improved, but our narrative is the same. As we’re wrapping the paper to send it to submission, however, I’m stuck. For the comments we have gathered this past year are pulling the takeway of our research in opposite directions.

“Urban economics looks just like macroeconomics to me,” one commenter writes, “fragmented, with many professional associations and fora. I don’t see fields that would be more unified. Development? IO? ” I have sometimes thought of urban economics as equivocal, a bustling field in the 1960s, almost disappeared in the 1980s, which then became a province of geographical economics only to reclaim a distinctive identity 10 years ago. And I view macroeconomics as just the opposite: uncontested objects (aggregate unemployment, inflation, business cycles), a changing but well-defined set of models and tools, members who unambiguously identify as macroeconomists, boundaries. When microeconomists showed impatience with macro models in the 1980s and 1990s and sought to explain the high level of aggregate wealth in the US and UK through looking at demography, precautionary savings or various types of heterogeneity, they knew they were trepassing. But for Paul Krugman, urban economics at the turn of the 1990s was just a small “peripheral field,” and what mattered was space and agglomeration, not the city. No need to knock at the field’s door.

“As I read through your material,” another commenter counters, “I come away with the impression that what you call urban is usually little more than a topic within some other, often slightly more established, field/branch of economics: labor, public finance, development.” There’s some truth to this, for sure. A lot of urban economics in the 1960s and 1970s was local public finance; it was about market failures, federalism, Tiebout sorting, land taxes and Henri George theorems (likewise, a large part of environmental economics at around the same time could be seen as mere applied public econ). Another chunk was about discrimination and possible mismatch between where black workers live and work. So applied labor it was. The topics discussed in urban economics seminars have changed: suburbanization in the 1950s, segregation, pollution and congestion in the 1960s and 1970s, gentrification, urban sprawl, edge cities and crime in the 1980s and 1990s. The methods have changed as well: from partial to general equilibrium and monopolistic competition models in theory. From gravity models to hedonic pricing and discrete choice models to shift-share IVs. But all these methods have been imported. What tool did urban economics ever export, or produced for itself? On the other hand, urban economics has its own journal, founded in 1974 – ironically, its first editorial warned that “Urban economics is a diffuse subject, with more ambiguous boundaries than most specialties. The goal of this Journal is to increase rather than decrease that ambiguity.” It has its own code, its own textbooks, handbooks and courses (though always shared with regional, residential, etc), its own professional societies (same), even its own foundational texts, which we used in our empirical design. These are what historians and sociologists consider as the institutional markers of a field.

So I’m left with an evergreen question: when is an economic field a “field,” and not just a “topic”? Anthony came to urban economics as part of his dissertation work on the relationships between economists and geographers in the 20th century. But I came to it through thinking about fields, hot and cold. And in the 1970s, urban was the hottest of all, everyone was writing about it. I’ve been chewing on the topic vs field distinction for 10 years, my old blog tells me. That’s why I researched the history of the JEL codes. It’s the field map. Getting a code is the paramount sign you’re arrived, as a field. When I was done, I turned to writing field histories. I began piling up material on urban, public, environmental, agricultural, market design. “Fields are more signeposts than fences,” the AEA website reads. Sure. But that’s how recruitment and publication work. That’s how economists’ identity is organized. They identify as macroeconomists, labor or health economists. Or at least they do macro, public or development, opening fences and crossing fields as their careers go, like hobbits wandering around the Shire. That’s why it mattered, I thought, to write the history of their fields. But now I’m not so sure. Maybe a field is not a meaningful object for a historian after all. Too slippery.

What distinguishes fields from topics, I think, is foremost a sense of permanence. Topics are tied to new phenomena to explain, new questions to answer and most importantly, new problems to solve. Growth, unemployment, inflation, competition, development are old topics. Race, covid, inequality, crime, climate change are newer ones. A topic gets institutionalized as a field when it becomes clear that the problem or phenomenon is of permanent interest. A first set of topics got institutionalized as fields in the late 19th and early 20th century. These were topics that I call “native” to economics, for lack of a better term. Those topics that no one would dispute are for economists to sort out. A second set of topics got institutionalized around the 1970s, and these were “non-native”: health, education, law, environmental, topics that were previously the realm of other disciplines. This included urban. “The city” was not a topic economists thought that they had much to say about, before the 1950s. This period was also when new fields centered, not on topics, but on distinctive methods, emerged: behavioral, experimental, computational. (Experimentalists were weary of getting their own JEL code. They feared becoming visible yet separate meant that they would be isolated. Claiming that their methods applied to every field seemed a more promising strategy.) And it’s not over. Sport economics got a JEL code in 2019 and political economists have recently rejoiced about snatching the P in the classification.

Of course, while topics became entrenched in fields, their boundaries kept moving. Public finance once covered stabilization policies, Musgrave decided, but the topic was expelled from public economics as Tony Atkinson, Joe Stiglitz and others narrowed it down around the positive and normative analysis of taxation (and expenditures). It’s not always clear why some topics become fields, and some don’t. Why is health a field, while inequality isn’t? Is crime one? For this entrenchment, as I know from the JEL codes archives, and now from the urban economics mess, always came with a question: what’s the right level of analysis, the right object. Is it the city? Or region? Or space? Or Agglomeration? Or maybe transportation, or housing, are more consistent topics. They too, got their societies and journals and textbooks.

This leads me to what I think is the second, and more problematic, ingredient of fields: the underlying sense of distinctiveness, independence, or autonomy. Fields get established, not only when economists sense they’ll have to work on a topic for decades or centuries, but also when they believe that it will take distinctive approaches and conversations to pin them down. Urban economics was essentially organized by urban planners, economists, and most important patrons, who believe urban ills were so complex that they required a specific type of analysis.

A nice statement of this view is offered by an economist who wasn’t even a urban specialist, Jim Buchanan. In a recent account of Buchanan few contributions to urban economics, Dan Kuehn points to a talk that the public choice theorist gave around 1968. In it, he advised agricultural economists to emulate urban economists in defending their independence. He explained that:

“the presumption is that the very fact of urbanization, the concentration of people in space, itself modifies the economic constraints on behavior in such a manner as to warrant specialized consideration.”

Ironically, Buchanan’s remark was more the perfect argument for Krugman to legitimize, 30 years later, the development of a New Economic Geography than a defense of an independent economic analysis of the city.

The problem with tracking distinctiveness is that this series of ‘non-native’ fields was established precisely as a push for standardization swept the discipline. Applied fields were summoned to reshape themselves around a common theoretical core, usually a general equilibrium (or at least microfounded) workhorse model. Some old fields transitioned (think New Classical and RBC in macro, Diamond-Mirrlees in public economics. Some new were born this way (think Arrow in health). Some had separate funding streams, policy networks and education programs resilient enough to go rogue (development; agricultural). Urban had the Alonso-Muth-Mills model monocentric model, but it wasn’t a general equilibrium model explaining location and land rent, the size of cities, their boundaries. Residential economists succeeded where urban economists at large failed, with the Rosen-Roback model. This threatened the new field further. Urban was stuck, and so am I, because the thirst for distinctiveness inherent in field institutionalization, the push for standardization fueled by the stabilization of rational choice and general equilibrium theory, and the threat of fragmentation are in tension. This generates a lot of noise.

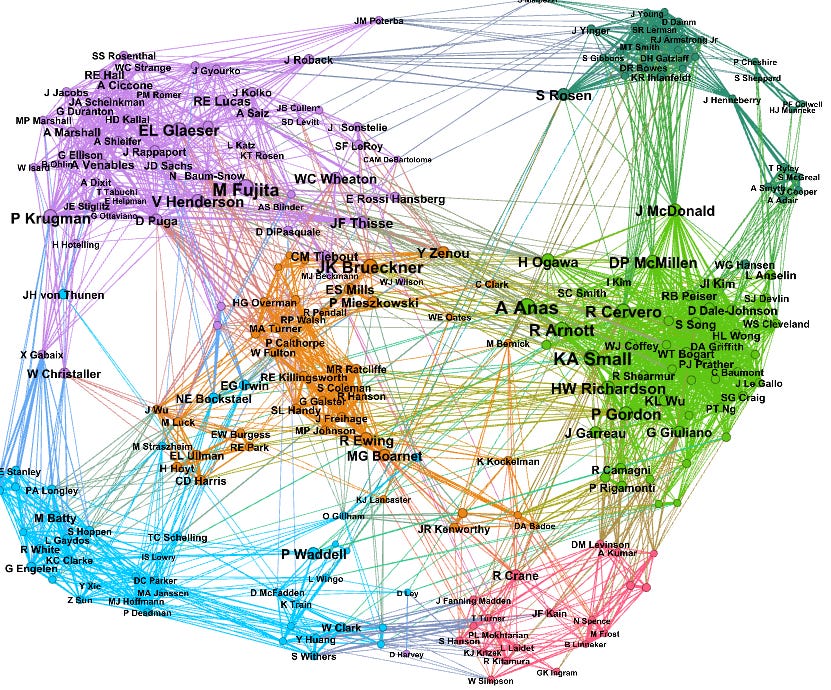

A further difficulty lies in the mix of native and non-native researchers that have populated urban economics since the 1950s. As an illustration, here are two of the networks of urban economists that Anthony and I have worked out (the database is all the articles and books cited in Web of Science article that also cite at least one of the Alonso (1964)-Muth (1969)-Mills (1967) trifecta, and what you see is how often these authors are cited with one another over periods of 5 years. Long story short, this is a method that does not allow us to map exhaustively urban economics, but to map work that are unmistakably associated to it).

What these networks and the archives we pair them with show is a phenomenon that I had never carefully thought about: the coexistence of contributors who would call themselves urban economists (Kain, Mills, Quigley, Wingo, Richardson, Henderson, Fujita, Brueckner, Arnott, Anas, Glaeser among others) with visitors from other fields. Some never really meant to contribute to urban, their work became relevant as they help urban economists to address specific issues (Tiebout, Becker, Schelling, Reid, Rosen), but other purposively entered the field at some point, with the goal of proposing a workshorse model that answers key questions about the structure, size or location of cities, or their hierarchies. Solow and Mirrlees did so in the 1970s (and failed). Krugman did in the 1990s and succeeded in subsuming urban economics into his New Economic Geography. At least for a while. Recently, some economists have reclaimed the city as a distinctive object. I also see a similar dynamics at play in the history of environmental economics (Krutilla, Kneese, d’Arge, Daly or Nordhaus vs Baumol, Solow again, Stiglitz, Coase and I wonder whether it does shape fields in specific ways. I also wonder what the respective consequences of importing theoretical model vs empirical tools from other fields are.

So field or topic. What is it that I’m chasing?