The economics profession is experiencing its third #metoo moment. The first one was in the 1970s, it was a general reckoning of the institutional and individual hurdles faced by women trying to become economists. The second one was started in 2017 by a research by then Berkeley undergraduate student Alice Wu. She documented awful sexist biases on EJMR, the anonymous platform where economist meet to discuss rumors, to complain about the state of the profession and increasingly, to offload their incel frustrations and air conspiracies. It led to profession-wide discussions about norms and priors in recruitment, promotion, supervision, coauthorship, editorship, and how credit, visibility and rewards are assigned in economics. Various departments and professional associations, among which the AEA, set up codes of conduct, reporting and investigative processes, and sometimes to hire ombudspersons.

The third one resulted from the 2022 “Nobel prize in economics” being awarded to someone who faces allegations of sexual misconduct, as well as a high-profile experimental economist being accused by a colleague. These allegations were taken up by some women economists on twitter who believe that the AEA actions to deal with widespread sexual misconducts faced by women in the profession were unfruitful. The awareness spread out, ironically, in part because specific information of the accused was reported on the aforementioned EJMR anonymous cesspool.

Bad Apples or systemic problem?

The first move was to gather testimonies and evidence on the “bad apples.” But these past days, many economists have asked how such behaviors have been allowed to persist for decades, systematically unpunished, unreported and unchecked. Women were left relying on the whisper network to avoid dangerous interactions. The role of the well-known unusually strong hierarchical structure of the profession in fueling power imbalances and their tragic consequences on women’s safety, as well as fear of retaliation, has thus been highlighted more often this week than during the 2017 discussions, or to compare with a more intellectual type of soul-searching, the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis.

And systemic or structural imbalances are indeed key to forging enduring shields against sexual harassment, gender biases, racism etc. Because it’s a long-term battle. #Econtwitter is rejoicing that women in the profession are “having a momentum.” It’s not the first. The 1970s one lasted a decade before the representation of women in the profession stalled, even went backwards as wages gaps between male and female professors widened. The consequences of the 2017 reckoning are unclear, beyond the recruitment of one female assistant professor in each department, efforts to have one female speaker on panels (or at least discussant, or at the very least moderator), having a few more women winning the John Bates Clark (JBC) medal and one more, Esther Duflo, winning the Nobel. The only economist that I can think of who was held accountable also happened to be the only Black JBC medalist (this isn’t to say he wasn’t guilty, but I find problematic that the only one found guilty is a nonwhite). The present #econmetoo episode has already succeeded in raising awareness about what hundreds of women economists are experiencing, about the unconditional need to trust them, about to how to prevent such behavior. But it’s clear that it will take a while to deliver, if at all – in the end it’s about due process legal battles, and those are complex and prolonged. One question is how to build momentum, another is how to sustain it. People don’t stay aware, enduring change is usually built into institutions and professional culture.

I’ve been asked this week what longstanding changes are needed. I’m not sure, but collectively reflecting on this begins with understanding how we got there. So here are a few thoughts on the process that lead to the hierarchies within our profession and pervasive power imbalances – some already thoroughly investigated by historians, other more speculative.

The rise of Harvard, MIT and Chicago

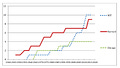

It’s essentially a story of how economists from three key places rose to dominance: MIT, Harvard, Chicago (with some additional central places appearing and disappearing across decades). Mostly in the US, but also worldwide, due to the internationalization process that Marion Fourcade and others highlighte. Andrej Svorenčík and I document a decrease in the institutional diversity of John Bates Clark medalists, with 25 out of 40 awardees receiving their PhD degree or worked at Harvard, MIT, or Chicago at the time of being awarded:

Svorenčík and Kevin Hoover likewise show that a growing share of the AEA electoral pool (AEA leadership + loosing candidates) got their PhD from MIT, Harvard and a few other institutions, and, to a lesser extent, have been employed there:

So how did we get there? Full-fledged research and anecdotal evidence together trace a post World War II path whereby students at top economic programs were taught to develop distinctive practices and modes of interactions, not only through courses, but also through advisor-advisee relationships and through attending workshop and conferences. They were carefully placed, sometimes re-hired at their home institutions, then nominated at top professional societies, policy institutions or academic journals. Matthew effects were also amplified by media attention, prizes and credit attribution. There are however differences between Harvard, MIT and Chicago. Harvard is one site that received less attention from historians. Perhaps because it has always been at the top, so there’s not much to explain beyond how it maintained itself (which other departments did not, but there’s always less historical research into marginalization processes). Best students in, best students out, with adding value relying more on individual strategies than collective visions. Here is how Kenneth Arrow described the differences between MIT and Harvard in 1975:

MIT and Chicago economists were perhaps more articulated in how to build, maybe not dominance, but a distinctive community. Several historians including Pedro Duarte, and myself, have documented how MIT economists consciously recruited small cohorts of graduate students. “This is a small department, which had decided not to get any bigger,” Bob Solow explained in 1963. MIT economists trained their students into writing small tractable toy models versatile enough to be applied to various economic issues. Who was the official advisor mattered little, the supervision was collective and faculty doors always open. Since the 1950s, when the department was still largely seen as providing support teaching to engineering students, the placement has been meticulous. As Duncan Foley later remembered, “they [at MIT] were so student oriented and interested in making sure that people would come through the department with what they needed to play leading roles in the discipline.” Solow wrote hundreds of recommendations letters. Though he counted among those few faculty members who advised a large number of students most (which Svorenčík documents is a pattern also found in other leading institutions, with MIT, Chicago and Harvard managing to re-hire their stars who in turned became prolific advisors), the lack of “personalization” contrasted with what could be observed at Chicago.

Workshop culture, networks, publications

Since the 1930s, Chicago economists had admitted large cohorts of students, who had to pass the landmark price theory courses, taught for decades by Milton Friedman, then Gary Becker. The point was not to train the students into a “style” of doing economics, as at MIT, but rather in how to use a “toolbox,” to use Ross Emmett’s words. Graduate students also acquired a debating culture, through a system of workshops that was built in the early 1950s. In Friedman’s workshop on money and banking, for instance, the game was to find “where the corpses are buried,” in Deirdre McCloskey’s words. The whole experience was more personalized than at MIT. Many students on track to become engineers, physicists or sociologists remember how foundational it was for them to attend Becker’s lecture, how clear and efficient they found his use of basic economic concepts. PhD defense, workshop presentations or more selective dinners were all about convincing Friedman (see for instance Steve Medema’s account on how Ronald Coase managed to convince Chicago to change its mind, or Arnold Harberger remembering a “fortress built around Milton Friedman and his views”).

I think that this personalization has persisted over time, and spread outside of Chicago, in particular in macroeconomics. A recurring memory I heard, when doing interviews, is one of a decisive workshop with Bob Lucas, Tom Sargent, Ed Prescott or else attending and vetting some article presented by young scholars. I don’t mean to say that any of them meant to exert power, just expressing their appreciation. Those reminiscences are very much about other researchers’ appreciation changing in the wake of such public vetting, with “you are arrived” comments, more publication opportunities, more invitations following. It’s a bitter irony that a profession who has contributed to busting the meritocratic myth by emphasizing how success derive from which neighborhood you grew up, how much economic, social and human capital your parents had, etc. still believes it for itself. It’s not just some of those who stand on top of the hierarchy who think they got here solely as a result of their intellectual brilliance. Most scholars down the ladder also believe so.

Aurélien Saïdi and I have recently surveyed workshop, conference and seminar cultures across the history of economics, and highlighted how these events have participated into building and perpetuating hierarchies. Alexander Gershenkron’s 1960s economic history seminar at Harvard was about students engaging in “dogfights,” trying to win an argument. Even before World War II, in the seminar that Lionel Robbins led at LSE, it was about who sat at the back and could gradually move to front rows, who managed to get “nods of approval from Robins and others” with a smart comment, and observing building hierarchies: “Hicks was the one to whom Robbins turned when discussion got though;” Abba Lerner “was the real star,” is the kind of remarks Sue Howson found in students’ mail from the 1930s. Those events were as much about inclusion as about exclusion, about who was invited to present at NBER seminars, who could attend prestigious dinners and who could not. They were also about staging disagreements rather than reaching a consensus, though some leaders like Elinor and Vincent Ostrom, for instance, explicitly aimed at fostering collaboration among equal through sitting around a large dining table (see Erwin Dekker and Pavel Kuchař on the history of the Ostrom workshop).

Is the dominance of economists trained at MIT, Chicago or Harvard in the AEA leadership a consequence of merit (aka intellectual superiority) or privilege (such as connections), Svorenčík and Hoover ask without providing a firm conclusion. They explain that some degree of preferential attachment exacerbates concentration, but also point that these two possible causes are difficult to disentangle. One related question is how economists from these few departments have crowded policy institutions such as the Council of Economic Advisors, the IMF, World Banks or ministries worldwide (there’s a ton of sociology of economics research in this, worth a separate post). This is also the case, I think, in the hitherto under-studied role of top journals in sustaining hierarchies. That a publication in one of the top-5 journals in economics is career-making has been extensively documented. One of these, the Journal of Political Economy, is edited by Chicago economists, with editors staying for decades. The Quarterly Journal of Economics had historically been handled by Harvard economists. Recent research has highlighted editors-authors networks. Last time I checked, in 2019, some high-profile economists were seating on the board of no less than 3 of these top-5 journals at the same time. Those who do so are usually dedicated researchers, who shoulder huge editorial burden as a service to the profession. But this concentration might affect editorial lines. I recently discussed the existence of tractability, computational and more widely epistemological standards in economics. Those economists from top institutions, generous as they are, have epistemological preferences for such and such type of model, for what’s a good proof, for what’s a convincing identification strategy, etc. They are disproportionately located in the US, which may also affect which topics and case studies are deemed worthy of publication, thereby contributing to make whole communities of economists in other parts of the world invisible. How networks of editors reinforce and stabilize those intellectual hierarchies is still understudied.

Prizes, media and the Matthew effect

Finally, those hierarchies are reinforced by citations patterns and how prizes are awarded. In 1947, AEA official thought that establishing the John Bates Clark Medal would mean trading internal resentment for external reinforcement of economists’ scientific credentials. They were right on both counts. The media, who like to cover scientific prize winners and promising geniuses, have since contributed to the Matthew effect breeding power abuses and fears of retaliations. Journalists routinely write “rise of lone genius” portraits of economists, in which the sneakers color or jeans fit are given more important roles than all those who painfully gathered the data or coded the softwares that made such research possible. Research achievements are never pictured as the result of teamwork, which is at odd which most of what history of science emphasize. Powering the lone genius myth also reinforce the twisted but widespread belief that tolerating bad behavior is the price to pay to get creative scientists, that talent is unescapably yoked to being an ass. The media is also inconsistent with respect to hierarchies. Just after spending a long year covering the 2017/2018 gender reckoning in the profession, The Economist published its “pick of the decade’s eight best young economists.” Not those that they thought “deserve a highlight.” No, the “best.” In other words, what the hierarchy whose deleterious effects they had unpacked the previous months should be. Beyond portraits of teams, I would welcome more investigation of how the media themselves make scientists visible or invisible (my own experience of interacting with journalists is perfectly gendered. All the female journalists I talked to ended up citing my work at some point – it can take time, I totally get it, I even enjoy longstanding conversations. None of the many male journalists I discussed historical insights and framing ever did).

This all point to where long term changes are needed: workshops/seminar rules and culture; diversity in editorial boards; governance of department, research institutes and professional associations; crediting practices; media.

Lots of good stuff here, but I don't see how it points to any problem in the economics profession. Why is this kind of concentration bad? It could easily be the result of increasing meritocracy, where the top departments hire the top people. Harvard and Yale in 1980, when I was a student, had a lot of deadwood, people who never were very good. I don't think that's true any more.

Is that the full document that Ken Arrow wrote? I'd love to read it if there's more!